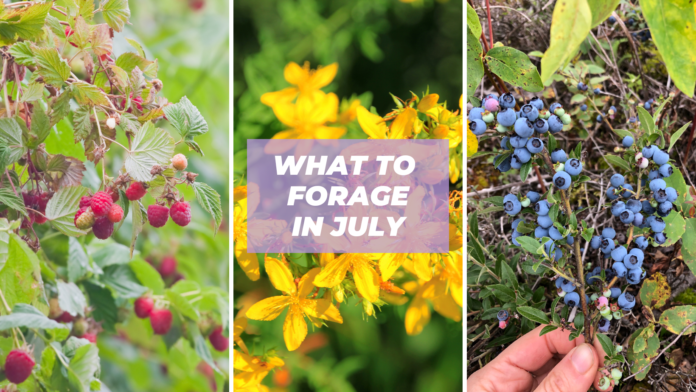

Late summer foraging is an exciting time to find edible berries, flowers, mushrooms and more! Get started with this guide for beginners.

In the dog days of summer, it might be hard to imagine there are any edible things left growing that are worth foraging.

Around here in New England, lawns are parched and the air is humid. However, believe it or not, these are the conditions some late summer wild edibles show themselves if you know where to look!

Below I’ll share some of my favorite plants and mushrooms to forage in the late summer that are easy for beginners to identify after a few notes and a disclaimer:

Please use caution when foraging plants for consumption. Do not eat plants you are not comfortable with identifying. See my plant identification resource recommendations below.

Note: I am foraging in the Northeast of the United States. While many of the plants can be found all over the world, some of them are specific to this region!

Alright, let’s get into it!

Hi, I’m Leslie, Founder of PunkMed!

Thanks for stopping by the blog to learn about late summer foraging! I am the founder being PunkMed, where I love to write about foraging, gardening, urban homesteading and all things plants! If you have any questions feel free to DM me on Instagram @lesliepunkmed. I love to hear from my readers! Happy foraging!

This post is all about late summer foraging.

Late Summer Foraging Edible Plants

Black cherry (Prunus serotina)

Black cherries are much darker than the sweet cherry you may find in the grocery store, hence the name. Black cherries have been enjoyed by Native Americans for centuries, but are largely ignored by modern peoples.

How to Find: Prunus serotina is widespread across the midwest and eastern United States. The black cherry is a deciduous tree or shrub that can grow to 50 to 80 feet tall. However, a young black will be thin, with small lenticels (horizontal markings) on its bark resembling birch. The leaves are long, ovate, shiny dark green, with finely toothed margins. White, five petaled flowers give way to large, dark fruit widely spaced out on long racemes (4–6 in).

How to Eat: Black cherries, like many cherries, can be enjoyed raw, but also make excellent jams, jellies, juice, and fruit leather.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Many might be hesitant to try a fruit with “choke” in the name. But, rest assured, chokecherry is completely edible and delicious!

How to Find: Chokecherries are highly related to the aforementioned black cherry–so much so that many don’t bother differentiating the two. However, chokecherries can be identified by their dull green broadly ovate laves with finely toothed margins and denser clusters of fruit–about 8-20 berries per raceme.

How to Eat: Wait until they are fully ripe and almost black before eating. The red berries can taste more astringent. Jelly and juice are probably the two most popular ways to enjoy chokecherry. To make a juice, place the berries in a pot with enough water just to cover and simmer until the berries soften. Strain and drink as-is or use for a jelly.

I have also used chokecherry juice to make a mead.

Elderberry (Sambucus spp.)

Elder (sometimes called elderflower or elderberry) are a common shrub or small tree found widely across the world. Most species (including the two found in North America, Sambucus canadensis and Sambucus nigra) have edible flower and berries, although the berries are only edible once cooked.

How to Find: Elder are common along roadsides and disturbed, sunny areas. The leaves are arranged in opposite pairs, pinnate with five to nine leaflets. In June, the shrub bears umbels of small, cream or white flowers that smell delicious and are edible. The flowers give way to dark purple to black berries in the late summer/early fall.

How to Eat: Elderberries are only edible once cooked. They make a nice syrup for ice creams and other desserts. Elderberry syrup is used in traditional medicine for colds and coughs. See my recipe for elderberry syrup.

Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata)

While the name is slightly confusing, as this plant is definitely not an olive and can be found in the late summer, autumn olive is one of my favorite foraged fruits! It’s invasive to the United States, so don’t feel bad about harvesting abundantly.

How to Find: Autumn olive is a deciduous shrub or small tree that can be found throughout central and eastern United State. Also known as silverberry, the leaves of the autumn olive are covered in silvery scales that later fall off in the summer. However, the undersides of autumn olive leaves will still be quite silvery. The berry is small (1/4 -1/3 in), round, bright red and juicy, with silver or brown speckles. The skin of the autumn olive berry is quite thin, giving it almost a translucent appearance.

How to Eat: My favorite way to eat autumn olive fruit is out-of-hand. However, you can certainly use them to make jellies or jams. I’ve heard of autumn olive being used as a substitute for tomato, giving its sweet-tart taste and abundance of lycopene.

Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina)

Staghorn sumac is the species common in the eastern U.S., but sumac (Rhus spp.) is found all over the world. Sumac is a popular spice in Middle Eastern countries, and is an ingredient in the spice blend za’atar.

How to Find: Sumacs are an abundant shrub in the eastern U.S. They are perhaps most easily identified in the summer when their hairy red fruits ripen in dense clusters.

How to Eat: Sumac fruit has a tangy taste thanks to its high malic acid content. Sumac fruit can be dried and used as a lemony spice. Many also like to make “sumac lemonade” by steeping the fruit in cold water, straining, and sweetening with sugar or honey.

Giant puffball (Calvatia gigantea)

Giant puffballs are probably familiar to many as the alien soccer-ball sized fungus that they kicked around as a kid. But, giant puffballs are also edible and are a great source of protein!

How to Find: Giant puffballs can be found throughout temperature regions across the world, in fields, forests, and along foot trails. As the name suggests, giant puffballs can be huge–up to 8 to 20 inches to be exact. Puffballs are round to oval-shaped, completely solid, and lack gills.

How to Eat: Giant puffballs should only be eaten before they have matured and are still perfectly white. When harvesting a giant puffball cut through the mushroom where it was attached to the ground. If it is yellow or greenish, it is to old to consume.

Puffballs are commonly battered and fried, but they also make for a great meat replacement and can act a lot like tofu in vegan/vegetarian dishes.

Hen-of-the-woods or maitake (Grifola frondosa)

Hen-of-the-woods or maitake is a popular mushroom in the culinary world. Lucky for us, it can be foraged throughout much of the United States. It is especially common in the Northeast.

How to Find: Maitake is a polypore mushroom that grows at the based of old-growth trees like oak and maple. Hen-of-the-woods appears as a cluster of grayish-brown caps with wavy edges. Check the underside–polypores DO NOT have gills.

How to Eat: Maitake makes an excellent stir-fry mushroom.

Lobster mushroom (Hypomyces lactifluorum)

Lobster mushroom is neither a lobster or a mushroom, but rather a parasitic fungus that infects mushrooms and turns them its characteristic bright color. (And changes its shape and flavor!) Might not sound yummy, but give it a try!

How to Find: Lobster mushrooms are so named for their reddish orange color and shape that resembles a lobster’s tail.

How to Eat: Do not harvest old lobster mushrooms that have produced spores (looks like white powder) or have a strong fishy odor. Believe it or not, lobster mushrooms actually do have a mild seafood-y flavor. Their dense texture make them an excellent meat replacement.

This post was all about late summer foraging.